The book “Thinking Fast and Slow” talks about cognitive biases, memory lapses, and the brain’s two hemispheres that are at odds with one another and how this causes you to make a wide variety of mistakes in perception, remembering, and decision-making, as well as how to correct these issues.

Intelligence is not only the ability to reason; it is also the ability to find relevant material in memory and to deploy attention when needed

Daniel Kahneman

In his book “Thinking, Fast and Slow,” Daniel Kahneman makes a convincing case for how easily we deviate from rationality and how our innate biases cause us to repeatedly make inept (to put it gently) irrational decisions. He argues people are basically illogical, making logical mistakes but also being somewhat predictable. Others might not think of this as a book for light reading, but Kahneman has made it accessible to anybody, regardless of their familiarity with psychology.

Because of our evolutionary background, we are predisposed to be overconfident in our ability to make judgments, which helps us to act quickly and confidently and avoid the sluggish paralysis that would arise from continual self-doubt. In this way, it’s difficult for individuals to accept the possibility that their own tastes aren’t uniform and unchanging. Therefore, it is not surprising that rational theory continues to support many policies in our society, despite the large body of experimental data showing otherwise. There is a lot to digest in thinking fast and slow, and it wouldn’t be fair to rate it just based on a synopsis, therefore no matter how much is included here, it will never be enough. Lets look at the core section which Kahneman discusses in detail in his book.

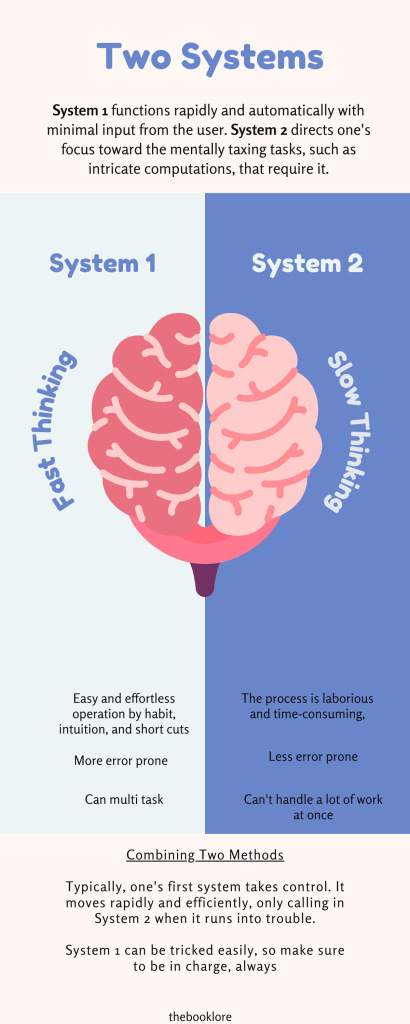

Daniel Kahneman talks explicitly about two systems through which we carry out the day-to-day tasks in the book. Just what is the answer to the question “what is 1+1?” Obviously, 2 is the first number that springs to mind. And what is 27×84? It will take some effort, but it is easy to figure it out (Answer: 2268). He constantly talks about how thinking is key to the systems. According to him, there are two systems. One’s speed of thought may be attributed to System 1, an ‘automatic’ system based on one’s intuition. There is a second system that is not so automatic and requires calculation and effort to find the result. System 2 directs one’s focus toward the mentally demanding tasks that need it, such as intricate computations. System 2 is typically associated with the felt sense of control, decision-making, and focused attention when functioning. Although these two systems seem to be well-suited for navigating the world at first glance, they give rise to several issues. System 2 offers advantages but requires both mental and physical effort to engage. Because of this, it tends to blindly obey System 1’s directives and ignore the prerequisites. System 1 activates when System 2 would be more appropriate because we tend to trust our intuition, even if it may lead us to the wrong answers and the wrong conclusions.

Daniel Kahneman dismantles the credibility of this view in Thinking, Fast and Slow and warns of the dire social consequences of adopting it. He describes in clear and thought-provoking detail the many cognitive biases and heuristics that all share; the many idiosyncrasies and intricacies that set us apart as a species.

In this section, Kahneman talks about preconceived notions and mental shortcuts (heuristics) that might lead us to make hasty judgments. Although System 2 thinking is more accurate in most cases, as Kahneman points out, we think more slowly when we are stuck and don’t have a quick answer to leap to (as when trying to solve the equation 27×84). Many of us are guilty of not bothering to question our initial assumptions when a rational solution reveals itself. And because of this, we might be tempted to make hasty decisions and end up taking shortcuts.

Why do we use Heuristics?

It can be because of several reasons, but three things come to mind

Affect Heuristics – Affect heuristics consider the excellent and negative emotions triggered by a stimulus. It is characterized by intuitive, knee-jerk reactions based on preconceived notions. For instance, when individuals are in a good mood, they are more likely to recognize the upsides and minimize the downsides of a decision. However, when people are sad, they are more likely to dwell on the potential drawbacks of choice than on its advantages.

Representative Heuristics – If we determine the likelihood of an occurrence by comparing it to the likelihood of another event, we are engaging in a representative heuristic. When deciding how likely something is, we typically base our judgment on how similar it is to a mental template we already have. If the said event happens, then we often need to account for the base rate or the real chance of an event occurring regardless of its similarities to prior events.

Availability Heuristics – Assumptions about the likelihood of an occurrence are often made based on whatever knowledge pops into one’s head first, and this is known as a “heuristic of availability.” Amid a debate, you may suddenly recall a slew of personal experiences that are highly instructive and that can help you in your present situation. Or, you may check the clouds to see if it’s going to rain before deciding whether or not to bring an umbrella, and you suddenly remember that there had been random showers throughout the week, and you decide to take the umbrella, anyway. These tricks of the mind help us make snap judgments, but they also have the potential to lead us astray.

He talks about various kinds of biases and constraints that can affect our decision-making –

There is a statistical oddity called the rule of small numbers that plays a critical role in making sense of data. In a nutshell, it emphasizes that little fluctuations in a small sample might have a significant impact on the results of an investigation. When dealing with a few subjects, biases become more pronounced. People place too much stock in the results of pilot research. It’s not reasonable to form an opinion based on the feelings of only five people who are unhappy with the country’s status right now, right? All you know is that they have some really ingrained prejudices.

Priming is the process through which our brains form links between concepts using cues, such as words. Almost every stimulus can trigger a shared memory and influence our choices. Nudges and advertisements with upbeat images are based on priming, which Kahneman explains. We can instantly connect words like “banana” and “yellow” in our heads because of the amazing associative power of the human brain. Not only can we remember things via color, but we can also remember them through well-known phrases, such as “the happiest place on earth” by Disney, “just do it” by Nike, or “Expect More. Pay Less” by Target. Whenever someone says the former, we relate that to their brand names.

Anchoring occurs when people place disproportionate weight on the first piece of information they encounter while deciding. When creating plans or projections, we tend to look at new information through the lens of our anchor rather than perceiving it in isolation. For example, You discover online that the going rate for the kind of laptop you’re looking for is around $2,500. The identical laptop is offered to you by a dealer in a physical store for $2000, which you will gladly accept because it is $500 less than what you had budgeted for. The only catch is that the other shop in town sells the identical laptop for only $1500, which is $500 less than what you spent and $1,000 less than the average price you discovered online.

As a sort of cognitive bias, the sunk cost fallacy causes us to misperceive data and steers us toward poorer choices. The sunk cost fallacy causes us to make poor judgments that cost us. When we don’t use reasoning, we get sucked into a loop of commitment where we keep putting in more and more effort, even when it’s not beneficial to us. The greater the stakes, the deeper our commitment, and the more energy we waste on a poor choice at the outset. Whether working at a toxic company or draining your energy on a person who doesn’t want to change, sunk cost fallacy is prevalent in today’s society.

Kahneman kicks off this part by introducing the notion of “What You See is All There Is,” which states that we form opinions based solely on the information at hand. People have the propensity to draw judgments without sufficient facts and are notoriously poor futurists. He also talks about the illusion of skill, where he talks about how people often feel that they are better or know more than they do. People who exaggerate their abilities are disappointed by reality.

Humans, Kahneman argues, are risk-averse, meaning that we shy away from danger whenever possible. Most people don’t enjoy taking risks because they worry about getting the worst possible result. We avoid risky situations as much as possible. Loss aversion is another idea presented by Kahneman. Many of the choices we confront in life carry with them both positive and negative outcomes. One can lose, and one can win. It permeates many areas of society, such as implementing legislation and changes that redistribute advantages away from some people to provide them to others, even if this increases the utility for everyone. The fear of failure is much more powerful than the drive to succeed. As a result, many people set relatively easy, short-term objectives they work hard to accomplish. When short-term objectives are met, they slow down. Therefore, their findings may go against conventional economic wisdom. Kahneman elaborates on this idea by saying that success and failure are more motivating than wealth. Rather than focusing on the final destination, we should enjoy the journey itself because it is frequently more satisfying than the prize itself.

If there was one book that you would need to read, read, and some more read, then it has to be this book. It will allow you to reevaluate your perspective on the world and the factors that go into making important decisions. In any case, this is not a book to be skimmed, nor is it intended to be. It does a great job of raising consciousness about the myriad cognitive thinking ability that contribute to faulty evaluations and decisions. To understand how we were able to be so blind to our underlying motivations and to what was actually good for us, one must delve into the hidden hang-ups that plagued us. Knowing what to do next can help you learn more about the myriad of conscious and unconscious factors that go into making any choice. As we previously stated, Thinking Fast and Slow is a book that must be read and reread in order to grasp what it is attempting to convey.